Vintage women’s wristwatches offer more than charm—they reflect decades of horological innovation and shifting aesthetics. Swiss brands, in particular, produced exceptional pieces that balanced micro-mechanical precision with evolving fashion tastes. This guide explores their journey from ornate bracelet watches to refined icons of the 1980s, highlighting key designs, calibers, and contributions from pioneering women in the field.

Early Wristwatches: A Feminine Innovation

Although wristwatches are now ubiquitous, they began as accessories for women. As early as 1810, Breguet created a wristwatch for Caroline Murat, Queen of Naples. In 1868, Patek Philippe crafted one for Countess Koscowicz. These were lavish, jeweled timepieces—essentially miniaturized pocket watches worn on the wrist.

By 1889, Vacheron Constantin introduced a full-fledged ladies’ wristwatch with a diamond-set case and goddess-motif bracelet at the Paris World’s Fair. Such models were aimed at the elite and prioritized decoration over accuracy.

The 1920s–30s: Art Deco Elegance and Micromechanics

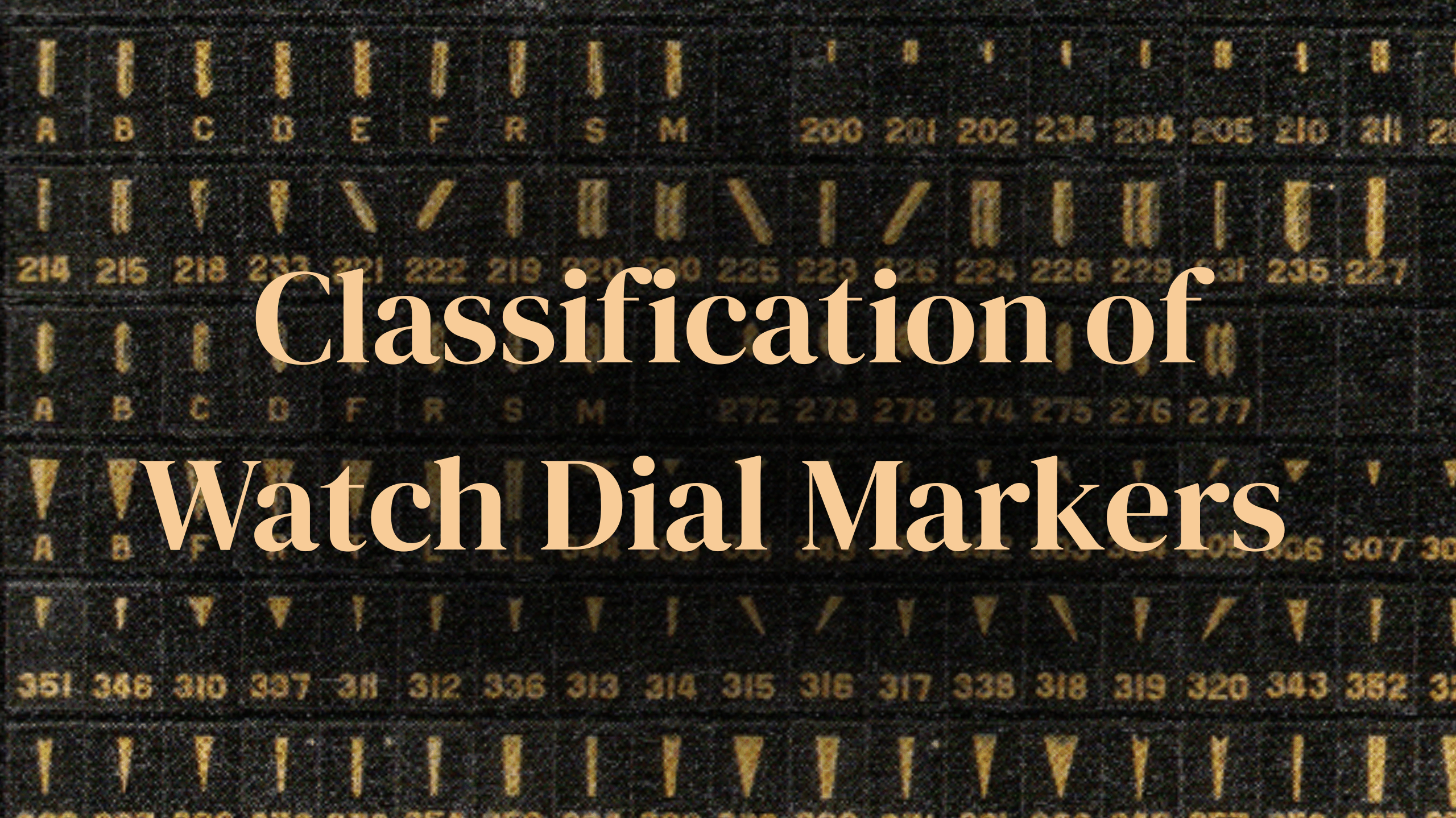

The rise of Art Deco design brought sleek geometries and luxurious materials to watchmaking. Square, rectangular, and tonneau cases in platinum and white gold were often set with diamonds and onyx. Hidden dials and "secret" watches, doubling as jewelry, became fashionable.

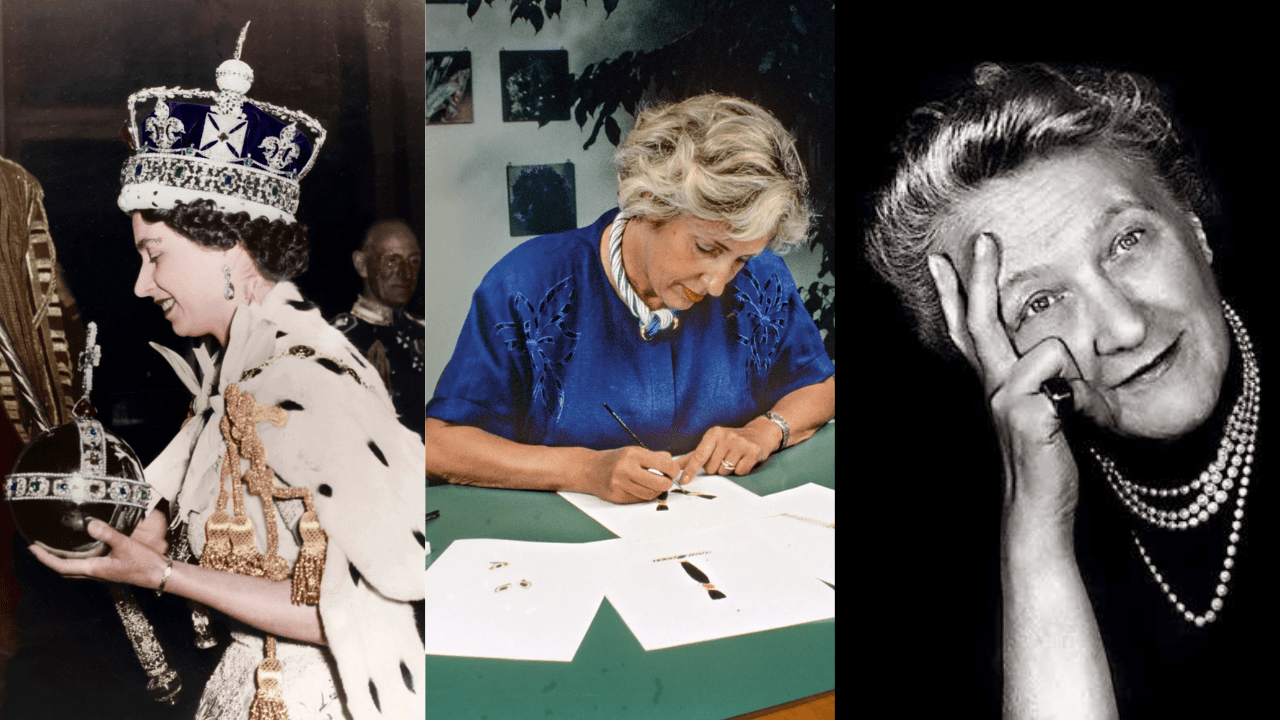

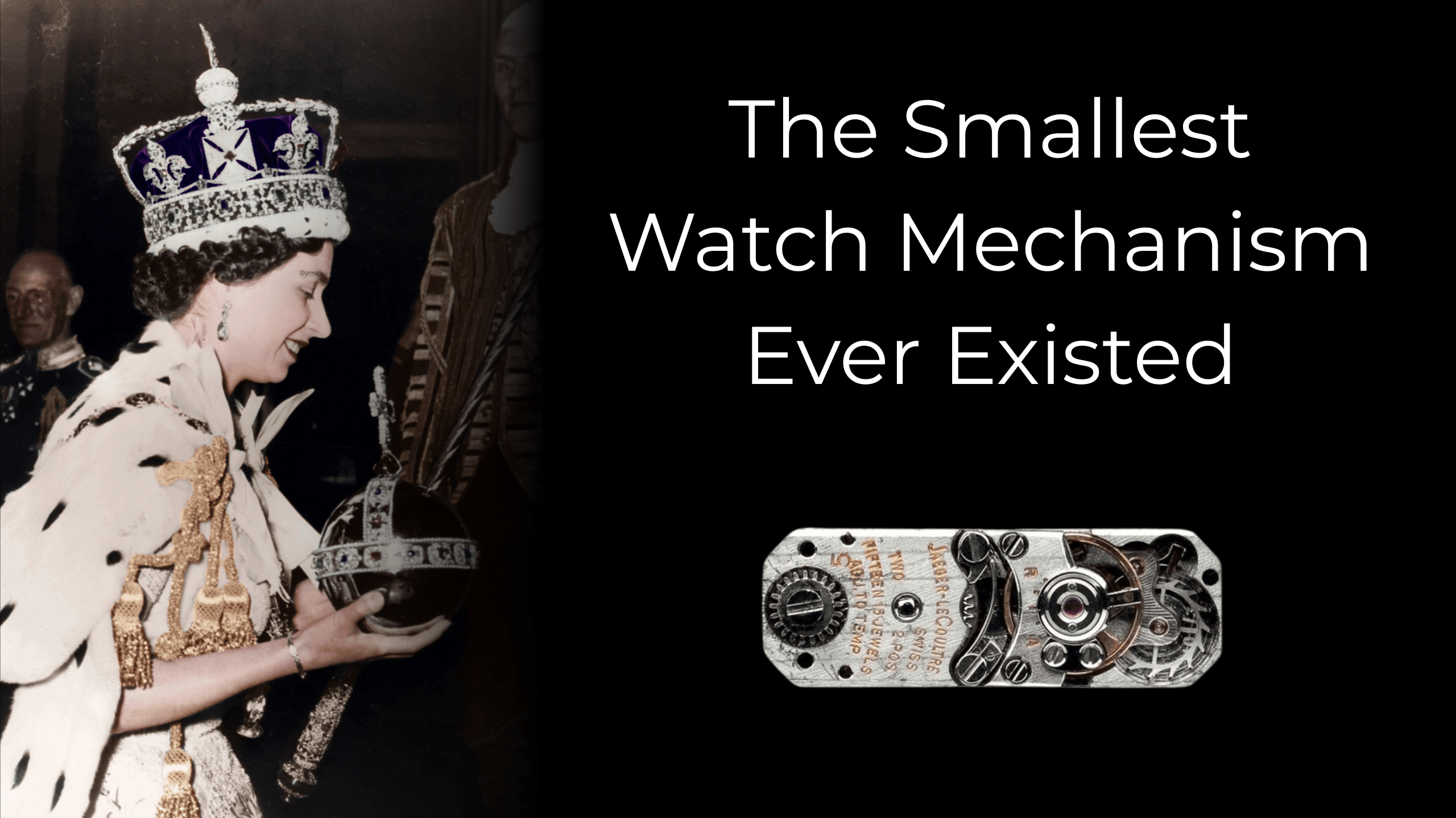

Technical strides followed suit. In 1929, Jaeger-LeCoultre launched the Calibre 101, the smallest mechanical movement ever made. Weighing less than a gram, it allowed watchmakers to shrink dials further while maintaining mechanical integrity. Queen Elizabeth II wore a Cal.101 watch at her coronation in 1953.

1940s–50s: Functionality Refined

The war era required more practical designs, but postwar watches returned to elegance—with subtlety. The 1950s saw delicate gold watches with minimalist dials, slim profiles, and tasteful embellishments. Omega’s Ladymatic (1955) stood out as one of the first automatic watches designed for women, housing a miniaturized self-winding movement.

Blancpain, led by Betty Fiechter—the industry’s first female CEO—was ahead of the curve. It introduced the Ladybird in 1956, featuring the smallest round mechanical movement at the time. These developments gave women watches that were technically advanced and stylistically elegant.

1960s–70s: Creative Expression and Quartz Disruption

By the 1960s, design freedom flourished. Women’s watches appeared in a variety of forms—from ultra-slim bracelet watches to bold cuff pieces. Omega’s Dynamic line featured oval cases, bright dials, and modular straps, aimed at a younger, fashion-forward audience.

The Quartz Revolution began in 1969 with Seiko’s first quartz watch. Swiss brands responded with ultra-thin, battery-powered models. Brands like Concord (with its record-thin Delirium) and Piaget pushed quartz to aesthetic extremes, creating jewelry-like watches with hardstone dials.

Yet mechanical watchmaking wasn’t entirely displaced. In 1976, Audemars Piguet launched a women’s version of the Royal Oak, designed by Jacqueline Dimier. She preserved Gérald Genta’s bold octagonal design while scaling it for female wrists—a landmark in unisex luxury design.

1980s: Quiet Luxury and Technical Resurgence

During the 1980s, high-end women’s watches gravitated toward refined minimalism. Models like the Rolex Lady-Datejust in two-tone steel and gold became status symbols among professionals. Piaget excelled in ultra-thin quartz models with lapis or onyx dials—understated but luxurious.

Quartz remained dominant, but a renewed appreciation for mechanical complications emerged. Women collectors began to seek chronographs, moonphases, and automatics. Swiss maisons responded with technically sophisticated women’s lines, recognizing that design and substance were equally important.

Contributions of Women in Watchmaking

Women have long contributed to Swiss watchmaking, often behind the scenes. By the early 20th century, they made up a significant portion of the workforce in tasks requiring finesse—movement assembly, dial painting, and finishing. Many enamelers and gem-setters were women.

Notably, Betty Fiechter (Blancpain) and Jacqueline Dimier (Audemars Piguet) helped shape industry direction in the 20th century. Their roles proved that women were not just consumers, but leaders and innovators. Dimier’s design of the Royal Oak Lady bridged traditional masculinity and emerging female tastes.

Iconic Swiss Models and Brands

Several models stand out as cornerstones of vintage women’s watchmaking:

-

Patek Philippe: Early wristwatches (1868), elegant Calatrava references, rare complicated pieces for women.

-

Vacheron Constantin: Art Deco gems, “secret” watches, and miniaturized baguette calibers.

-

Jaeger-LeCoultre: Calibre 101, Reverso Lady, and music-box novelties.

-

Omega: Ladymatic, Dynamic, Seamaster Saphette, Constellation Manhattan.

-

Blancpain: Ladybird, Rolls (early auto), and jewelry-grade timepieces.

-

Piaget: Bracelet watches with stone dials, ultra-thin movements like the 9P.

-

Audemars Piguet: Royal Oak Lady, early minute repeaters for women (1910s).

-

Rolex: Lady-Datejust (from 1957), cocktail watches, and sporty Oyster cases.

-

Cartier: Tank, Baignoire, Crash – combining Swiss movements with French design flair.

Why Collect Vintage Women’s Watches?

Vintage ladies’ watches showcase the heights of miniaturized craftsmanship, often with in-house mechanical movements rivaling those of men’s models. Their compact dimensions required clever engineering—tiny rotors, ultra-thin escapements, or shock-resistant innovations.

Moreover, these pieces often feature exceptional case and dial work: cloisonné enamel, stone inlays, and hand-set diamonds. For the enthusiast, a well-preserved mid-century Omega or a 1930s Vacheron “secret” watch isn’t just an accessory—it’s horological art.